JavaScript has changed quite a bit in the last years. These are 12 new features that you can start using today!

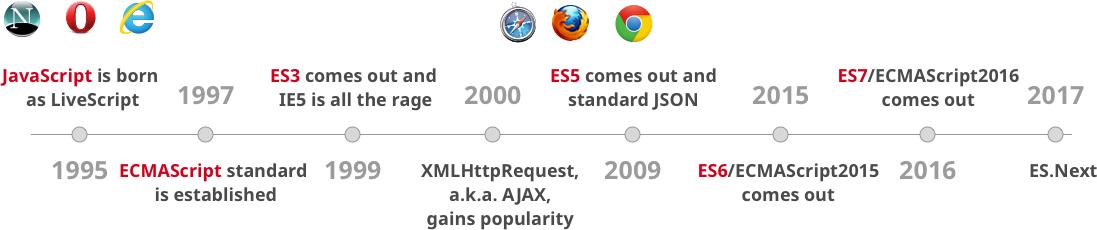

JavaScript History

The new additions to the language are called ECMAScript 6. It is also referred as ES6 or ES2015+.

Since JavaScript conception on 1995, it has been evolving slowly. New additions happened every few years. ECMAScript came to be in 1997 to guide the path of JavaScript. It has been releasing versions such as ES3, ES5, ES6 and so on.

As you can see, there are gaps of 10 and 6 years between the ES3, ES5, and ES6. The new model is to make small incremental changes every year. Instead of doing massive changes at once like happened with ES6.

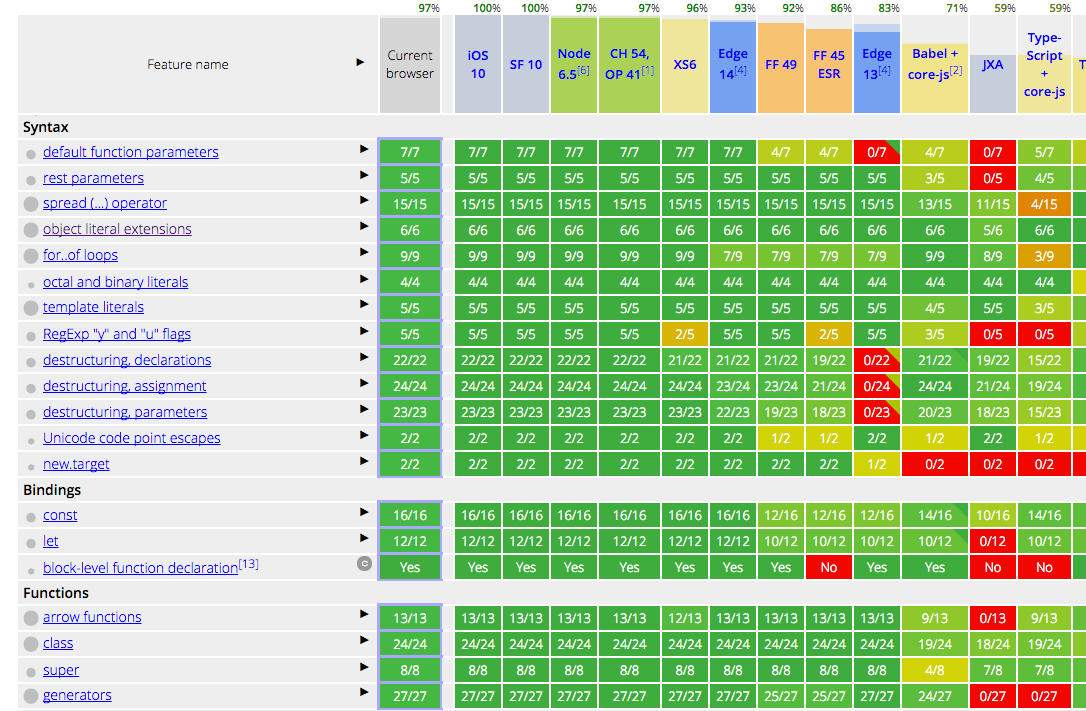

Browsers Support

All modern browser and environments support ES6 already!

source: https://kangax.github.io/compat-table/es6/

Chrome, MS Edge, Firefox, Safari, Node and many others have already built-in support for most of the features of JavaScript ES6. So, everything that you are going to learn in this tutorial you can start using it right now.

Let’s get started with ECMAScript 6!

Core ES6 Features

You can test all these code snippets on your browser console!

So don’t take my word and test every ES5 and ES6 example. Let’s dig in 💪

Block scope variables

With ES6, we went from declaring variables with var to use let/const.

What was wrong with var?

The issue with var is the variable leaks into other code block such as for loops or if blocks.

1 | var x = 'outer'; |

For test(false) you would expect to return outer, BUT NO, you get undefined.

Why?

Because even though the if-block is not executed, the expression var x in line 4 is hoisted.

var hoisting:

varis function scoped. It is availble in the whole function even before being declared.- Declarations are Hoisted. So you can use a variable before it has been declared.

- Initializations are NOT hoisted. If you are using

varALWAYS declare your variables at the top. - After applying the rules of hoisting we can understand better what’s happening:

ES5 1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9var x = 'outer';

function test(inner) {

var x; // HOISTED DECLARATION

if (inner) {

x = 'inner'; // INITIALIZATION NOT HOISTED

return x;

}

return x;

}

ECMAScript 2015 comes to the rescue:

1 | let x = 'outer'; |

Changing var for let makes things work as expected. If the if block is not called the variable x doesn’t get hoisted out of the block.

Let hoisting and “temporal dead zone”

- In ES6,

letwill hoist the variable to the top of the block (NOT at the top of function like ES5). - However, referencing the variable in the block before the variable declaration results in a

ReferenceError. letis blocked scoped. You cannot use it before it is declared.- “Temporal dead zone” is the zone from the start of the block until the variable is declared.

IIFE

Let’s show an example before explaining IIFE. Take a look here:

1 | { |

As you can see, private leaks out. You need to use IIFE (immediately-invoked function expression) to contain it:

1 | (function(){ |

If you take a look at jQuery/lodash or other open source projects you will notice they have IIFE to avoid polluting the global environment and just defining on global such as _, $ or jQuery.

On ES6 is much cleaner, We also don’t need to use IIFE anymore when we can just use blocks and let:

1 | { |

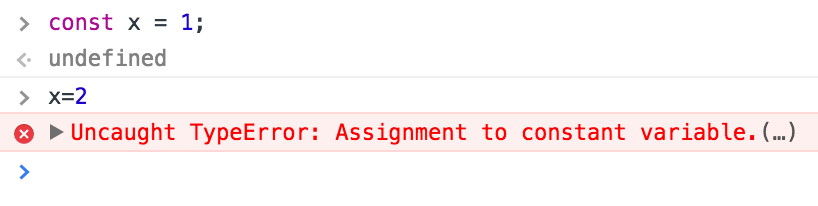

Const

You can also use const if you don’t want a variable to change at all.

Bottom line: ditch

varforletandconst.

- Use

constfor all your references; avoid usingvar. - If you must reassign references, use

letinstead ofconst.

Template Literals

We don’t have to do more nesting concatenations when we have template literals. Take a look:

1 | var first = 'Adrian'; |

Now you can use backtick (`) and string interpolation ${}:

1 | const first = 'Adrian'; |

Multi-line strings

We don’t have to concatenate strings + \n anymore like this:

1 | var template = '<li *ngFor="let todo of todos" [ngClass]="{completed: todo.isDone}" >\n' + |

On ES6 we can use the backtick again to solve this:

1 | const template = `<li *ngFor="let todo of todos" [ngClass]="{completed: todo.isDone}" > |

Both pieces of code will have exactly the same result.

Destructuring Assignment

ES6 desctructing is very useful and consise. Follow this examples:

Getting elements from an arrays

1 | var array = [1, 2, 3, 4]; |

Same as:

1 | const array = [1, 2, 3, 4]; |

Swapping values

1 | var a = 1; |

same as

1 | let a = 1; |

Destructuring for multiple return values

1 | function margin() { |

In line 3, you could also return it in an array like this (and save some typing):

1 | return [left, right, top, bottom]; |

but then, the caller needs to think about the order of return data.

1 | var left = data[0]; |

With ES6, the caller selects only the data they need (line 6):

1 | function margin() { |

Notice: Line 3, we have some other ES6 features going on. We can compact { left: left } to just { left }. Look how much concise it is compare to the ES5 version. Isn’t that cool?

Destructuring for parameters matching

1 | var user = {firstName: 'Adrian', lastName: 'Mejia'}; |

Same as (but more concise):

1 | const user = {firstName: 'Adrian', lastName: 'Mejia'}; |

Deep Matching

1 | function settings() { |

Same as (but more concise):

1 | function settings() { |

This is also called object destructing.

As you can see, destructing is very useful and encourages good coding styles.

Best practices:

- Use array destructing to get elements out or swap variables. It saves you from creating temporary references.

- Don’t use array destructuring for multiple return values, instead use object destructuring

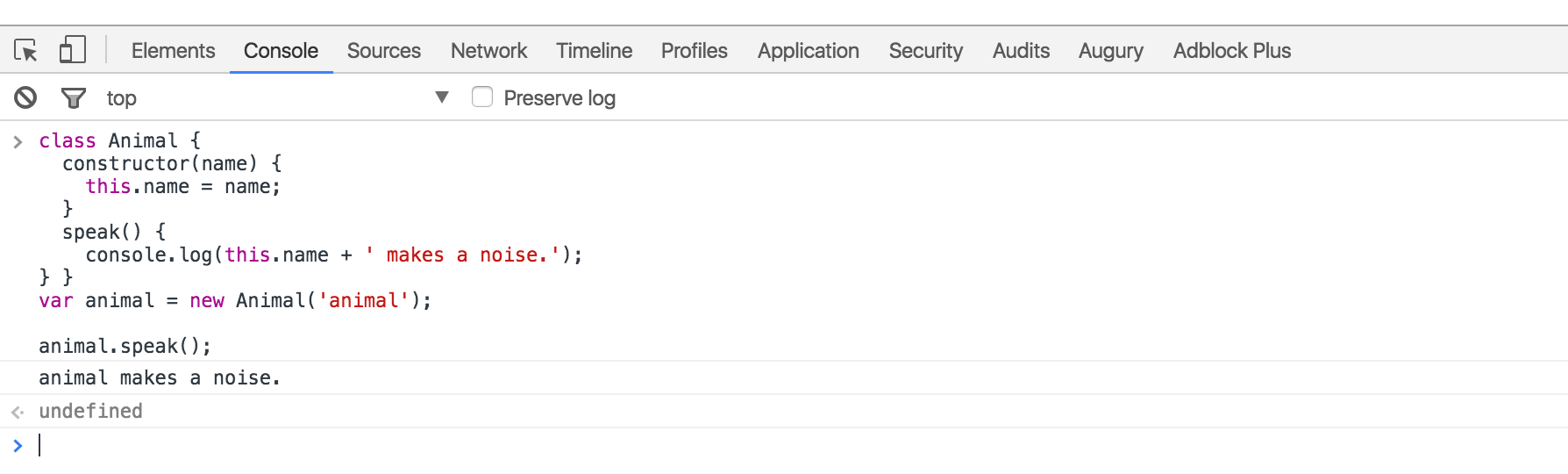

Classes and Objects

With ECMAScript 6, We went from “constructor functions” 🔨 to “classes” 🍸.

In JavaScript every single object has a prototype, which is another object. All JavaScript objects inherit their methods and properties from their prototype.

In ES5, we did Object Oriented programming (OOP) using constructor functions to create objects as follows:

1 | var Animal = (function () { |

In ES6, we have some syntax sugar. We can do the same with less boiler plate and new keywords such as class and constructor. Also, notice how clearly we define methods constructor.prototype.speak = function () vs speak():

1 | class Animal { |

As we saw, both styles (ES5/6) produces the same results behind the scenes and are used in the same way.

Best practices:

- Always use

classsyntax and avoid manipulating theprototypedirectly. Why? because it makes the code more concise and easier to understand. - Avoid having an empty constructor. Classes have a default constructor if one is not specified.

Inheritance

Building on the previous Animal class. Let’s say we want to extend it and define a Lion class

In ES5, It’s a little more involved with prototypal inheritance.

1 | var Lion = (function () { |

I won’t go over all details but notice:

- Line 3, we explicitly call

Animalconstructor with the parameters. - Line 7-8, we assigned the

Lionprototype toAnimal‘s prototype. - Line 11, we call the

speakmethod from the parent classAnimal.

In ES6, we have a new keywords extends and super .

1 | class Lion extends Animal { |

Looks how legible this ES6 code looks compared with ES5 and they do exactly the same. Win!

Best practices:

- Use the built-in way for inherintance with

extends.

Native Promises

We went from callback hell 👹 to promises 🙏

1 | function printAfterTimeout(string, timeout, done){ |

We have one function that receives a callback to execute when is done. We have to execute it twice one after another. That’s why we called the 2nd time printAfterTimeout in the callback.

This can get messy pretty quickly if you need a 3rd or 4th callback. Let’s see how we can do it with promises:

1 | function printAfterTimeout(string, timeout){ |

As you can see, with promises we can use then to do something after another function is done. No more need to keep nesting functions.

Arrow functions

ES6 didn’t remove the function expressions but it added a new one called arrow functions.

In ES5, we have some issues with this:

1 | var _this = this; // need to hold a reference |

You need to use a temporary this to reference inside a function or use bind. In ES6, you can use the arrow function!

1 | // this will reference the outer one |

For…of

We went from for to forEach and then to for...of:

1 | // for |

The ES6 for…of also allow us to do iterations.

1 | // for ...of |

Default parameters

We went from checking if the variable was defined to assign a value to default parameters. Have you done something like this before?

1 | function point(x, y, isFlag){ |

Probably yes, it’s a common pattern to check is the variable has a value or assign a default. Yet, notice there are some issues:

- Line 8, we pass

0, 0and get0, -1 - Line 9, we pass

falsebut gettrue.

If you have a boolean as a default parameter or set the value to zero, it doesn’t work. Do you know why??? I’ll tell you after the ES6 example ;)

With ES6, Now you can do better with less code!

1 | function point(x = 0, y = -1, isFlag = true){ |

Notice line 5 and 6 we get the expected results. The ES5 example didn’t work. We have to check for undefined first since false, null, undefined and 0 are falsy values. We can get away with numbers:

1 | function point(x, y, isFlag){ |

Now it works as expected when we check for undefined.

Rest parameters

We went from arguments to rest parameters and spread operator.

On ES5, it’s clumpsy to get an arbitrary number of arguments:

1 | function printf(format) { |

We can do the same using the rest operator ....

1 | function printf(format, ...params) { |

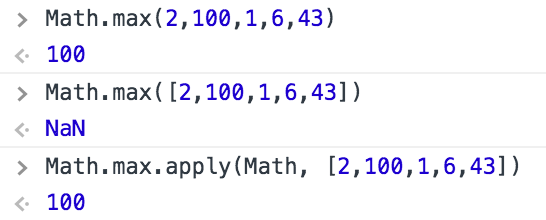

Spread operator

We went from apply() to the spread operator. Again we have ... to the rescue:

Reminder: we use

apply()to convert an array into a list of arguments. For instance,Math.max()takes a list of parameters, but if we have an array we can useapplyto make it work.

As we saw in earlier, we can use apply to pass arrays as list of arguments:

1 | Math.max.apply(Math, [2,100,1,6,43]) // 100 |

In ES6, you can use the spread operator:

1 | Math.max(...[2,100,1,6,43]) // 100 |

Also, we went from concat arrays to use spread operator:

1 | var array1 = [2,100,1,6,43]; |

In ES6, you can flatten nested arrays using the spread operator:

1 | const array1 = [2,100,1,6,43]; |

Conclusion

JavaScript has gone through a lot of changes. This article covers most of the core features that every JavaScript developer should know. Also, we cover some best practices to make your code more concise and easier to reason about.

If you think there are some other MUST KNOW feature let me know in the comments below and I will update this article.